Digital Drama invited project partners and volunteers to research and write blogs about the Endell Street Military Hospital; exploring its context within the First World War and the people who worked and were treated there. A huge thank you to all our contributors.

Author: Sara Haslam

Since 2015, I’ve been working on the story of Helen Mary Gaskell’s War Library. This prime example of what I call ‘literary caregiving’ was begun in London in the same month war was declared in order to help wounded soldiers. Gaskell’s vision was of a library stocked with donated books, communicating care from those in the UK who sent books at the same time as delivering, by literary means, distraction, entertainment, information, comfort, and relaxation for traumatised bodies and minds.

The War Library was incredibly successful from the outset. It affiliated with the Red Cross in 1915, which helped raise its profile as well as meaning it could operate more successfully. Until that point, May Gaskell, as she was known, funded the library along with her brother, Beresford Melville, and a few wealthy and influential friends, including some politicians. Lady Battersea offered her Marble Arch mansion, then standing empty, to house the donated books. Viscount Samuel, the Postmaster General, wrote later of his pleasure at heading the department responsible for administering the War Library’s national collections and international deliveries. Affiliation with the Red Cross opened the way to accessing better funding for the project, and The Times newspaper was particularly friendly to the library, carrying many advertisements and letters to spread the word. I tell the story of this library in an article forthcoming in the Journal of Medical History.

I came across Digital Drama’s projects on Endell Street Military Hospital online during my research. Endell Street also had a library, and I was interested in the links between these two war-time book-related ventures. I dropped an enquiry to Digital Drama’s contact address, and was amazed on Alison Ramsey’s reply to learn that she also works part-time at the Open University in London. She invited me to the immersive drama the company produced about Endell Street (which was a huge treat to see), and introduced me to Dr Jennian Geddes. Jennian’s article on Endell Street, ‘Deeds and Words in the Suffrage Military Hospital in Endell Street’, published in Medical History (2007), is a must-read for anyone working this field.

Endell Street’s library was run by two prominent members of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, founded in 1908 by Cicely Hamilton and Bessie Hatton. The aim of the WWSL was to obtain the franchise on the same terms as men, and it sought to do this through use of the pen. Elizabeth Robins, an American actress and writer, was one of the first members of the WWSL, and its first president. The British novelist Beatrice Harraden was another of the organisation’s first members and she served as librarian at Endell Street from 1915 until it closed, joined by Elizabeth Robins for the first year or so. The philosophy of this library, like Gaskell’s, was a reader-led one. In other words, these women made an operational decision to cater for the readers’ requests when it came to their reading matter, rather than to impose their idea of what might be termed ‘improving’ reading upon them. The wounded men’s fears of having their lack of education exposed, or of being made fun of for their tastes in more popular literature, for example, were eased in this way. The librarians’ seat at their bedside became an opportunity to enjoy conversation and experience care based on books and reading.

Books were part of the men’s cure, therefore, and their availability was part of what I see as care ‘in the round’ at this hospital. It is a pleasure to be working on this story as a literature specialist, experiencing during my research my own belief in the positive power of books becoming increasingly evidenced in this way. I’m writing up the results now in a co-authored piece on war-time bibliotherapy with my colleague Edmund King.

Digital Drama’s inspiring productions have proved to be a highlight of my research across this past year. Thanks to all involved!

Sara Haslam

Dept of English & Creative Writing

The Open University

www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/100-years-votes-some-women

Author: Charlie Forman

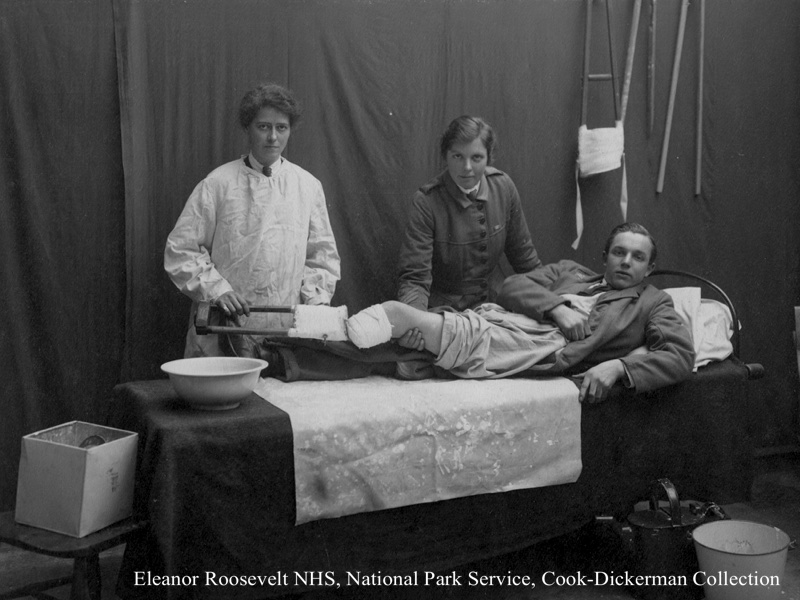

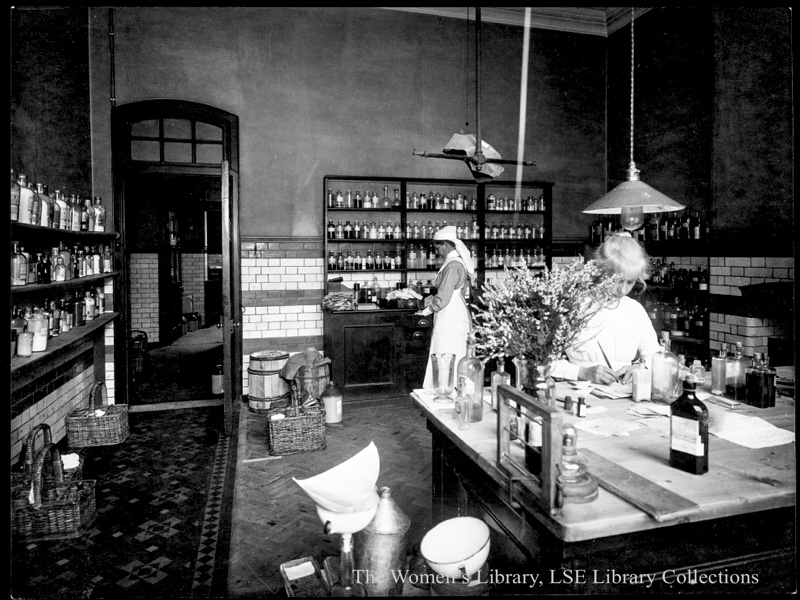

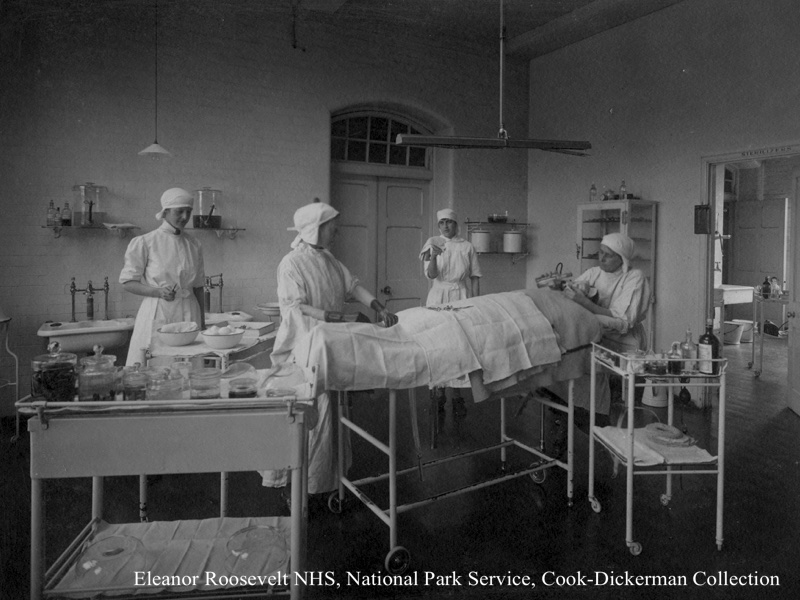

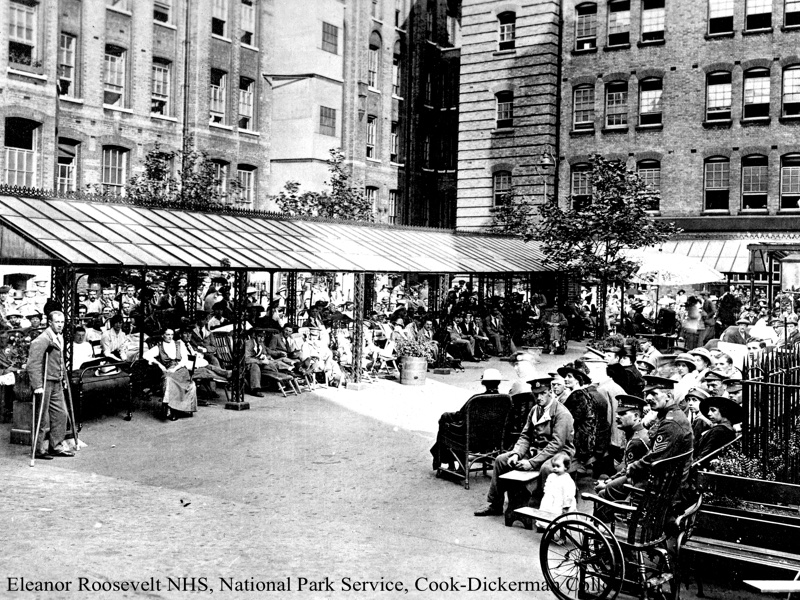

The women staffing Endell Street Military Hospital were closer to the Western Front than their Covent Garden address might suggest. Many of the hospital trains bringing troops from the south coast ended up within walking distance. At Waterloo or Charing Cross stations wounded soldiers were transferred to fleets of waiting ambulances. Proximity meant ambulances could do a quick turn-round. But it also offered near immediate surgical attention for the most seriously injured patients. So each time the Endell Street bell rang to announce another convoy of ambulances, staff scrambled to help move men – often with serious abdominal, cranial and orthopaedic wounds – from ambulance to ward as quickly and painlessly as possible.

Through the war, the army’s logistical connections with the London hospitals improved. When war broke out, London was entirely unprepared. For the first wounded soldiers arriving at Waterloo from Mons in August 1914, there were only enough ambulances for officers. Other ranks were left on the station concourse until 15 horse drawn Lyons bread vans were rustled up to take them to Whitechapel’s recently alerted London Hospital. Come the Battle of the Somme in 1916 there were fleets of hospital trains waiting. But for the 35,000 wounded on the Somme’s fateful first day- the highest casualty figure in British history – most of the trains were inexplicably in the wrong place. Ensuing delays caused many fatalities and extra complications for the surgeons waiting in London’s hospitals. Yet by June 1917, it was said that a soldier injured in the dawn assault on the Messines ridge might be in a London hospital that same night.

During the war there were 350 military and auxiliary hospitals in London. But it would be a mistake to see Endell Street as just one among the many. Very few had Endell Street’s operating capacity to handle arrivals straight from the front. In the vanguard were the five ‘general’ hospitals. Often planned, like Endell St, with 520 beds some were able to expand into surrounding open space creating wards out of single storey wooden huts. The one in Wandsworth even built a bespoke railway station. Endell Street’s very central constrained site prevented this. Instead they set up three convalescent hospitals in the suburbs for 250 patients. This increased throughput in the main hospital to the extent that each bedspace treated an average of 50 patients during the hospital’s 4 year life, accounting for 26,000 discharges in all.

Most of London’s auxiliary hospitals provided this second stage recuperative care, while some specialized either by medical condition or by the nationality or rank of the patient. (Officers were far more likely than other ranks to get a London bed). Measured by throughput, this leaves Endell St as one of the ten biggest military hospitals in London.

Plenty of other women made notable contributions in helping the war wounded. The women of Endell Street stand out as being an organisation of professionals, harbingers of women’s future role in the health service. Most of the others were in the thinning tradition of volunteers – donating their time, money and even property to the cause. Many of the hospitals were staffed by nurses from the Voluntary Aid Detachments. It is thanks to Beatrice Dent (nee Dimsdale), appalled by those scenes at Waterloo station in 1914, that money was raised from City institutions to pay for an adequate ambulance service. Meanwhile, more than a dozen aristocratic women donated their London town houses to become hospitals ‘for the duration’.

But as Queen Alexandra visited Endell Street in 1917 it is worth conjecturing whether the workforce would have been pleased or dispirited to know that it would take exactly 100 years for the number of women doctors to equal the number of men.

Author: Katya Creed

A huge thank you to Morgan Brewster, who got in contact with Digital Drama after picking up our project flyer in a Covent Garden pub when he was in the UK researching his great uncle Louis Daem’s story….

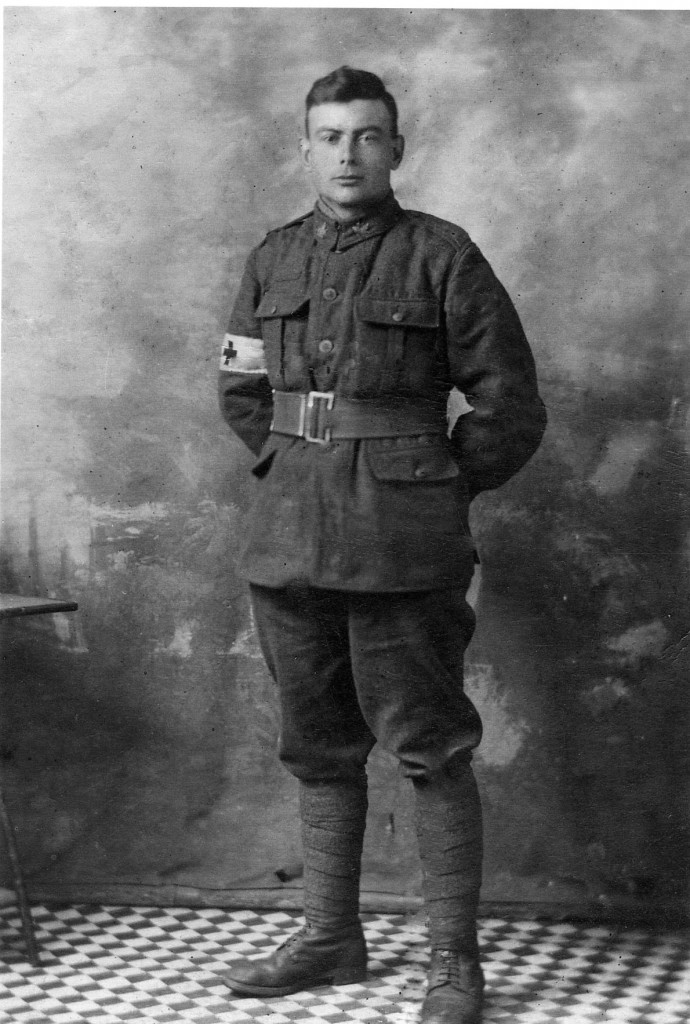

When Canadian Private Louis Daem arrived at the Endell Street Military hospital on the 7th November 1918, a blacksmith turned decorated war hero with shrapnel in his thigh, he was received with the same flurry of stretchers, linens and doctors that all those arriving to London hospitals from the front were familiar with. However, in this case, he was received exclusively by women.

We think we know the story, and we already know how it ends. But to get to the heart of the story, we have to go back to the beginning.

Louis Daem signed his enlistment papers and swore allegiance to His Majesty King George V in January 14, 1916 having travelled to Vancouver, B.C. He was 22 years old and had 6 siblings; 4 brothers and two sisters. At 5’ 9” tall with brown hair and brown eyes he was a striking young man. He had been working as a blacksmith prior to enlisting (a job that may have subsequently gone to a woman in absence of young men). The pay he received as a private was sent home at his request to his sister, Mary Daem.

Throughout his time at the front, Louis witnessed the very beating heart of this war, ranging from on the ground soldiering to aeroplane activity “resulting in several aerial duels.” By the age of 23 he had witnessed British planes falling in flames. The unpredictable changing pace of life at the front was no doubt disorientating. For days, he was stuck stagnant with orders to “stand to”, followed swiftly by constant aerial fighting and the subsequent difficulties of burying the wounded, maintaining the trenches and completing anti-gas precautionary measures. Every effort at all times was concentrated on successfully completing the most recently assigned tasks and missions.

On the 1st of November 1918 an intense barrage began, described as the most violent they had yet witnessed in France. The casualties were described as “frightful” with hundreds of prisoners captured. With sudden orders for assembly and movement, the battalion was moved immediately and within 30 minutes were on their way in support of the 10th Brigade. It was here that Louis earned his medal for bravery under fire.

On the 2nd of November, a concerted plan of attack was initiated, with the object of pushing back the enemy towards the east from the south of Valenciennes. The 102nd battalion fell into its place on the left flank of the 54th encountering considerable machine gun opposition. Despite this, they successfully pushed forward to their objectives, but not without casualties. Amongst these casualties was Private Daem.

Having been surrounded by bullets, shells, gas and death for two years it would be hard not to think of oneself as invincible. When there is so much to be afraid of, one stops being afraid at all. Throughout the course of his military service, Louis had been hospitalised for mumps, influenza and gonorrhoea – but this was his first and only case

Throughout those intervening days, Louis was rapidly evacuated and within 4 days had reached Brighton, passing through field hospitals and clearing stations. All of which would have been improvised structures. On the 7th of November, 5 days after being wounded, Louis was admitted to the Endell Street Military Hospital in Covent Garden. The staff noted that on admission he was “very shocked”, a reference to his shell shock, and appeared nervous. More worrying, his wounds were “very septic.” Four days after his treatment began, an armistice was signed and after 1568 days of fighting The Great War was over.

Once away from the dangers of the front, Louis was able to finally receive proper medical treatment, all of which was documented by the Endell Street doctors, orderlies and administration staff. He underwent two operations, which included an amputation. He was supplied with copious amounts of brandy in place of traditional painkillers as supplies were stretched to their limit. Louis battled his infections in this way for 32 days, but eventually succumbed to his injuries. On the 21st of November, 1918, his condition was steadily worsening. His pulse was rapid and a few days later a large abscess had formed in his thigh. The hospital administered saline intravenously, after which his pulse rate improved. A few days later on the 9th December the doctors of the Endell Street Military Hosptial operated on his wounded thigh, removing his leg in a full amputation. Despite his steady pulse and another round of saline Louis collapsed shortly after his surgery. He was recorded as having died of heart failure.

It’s a story we are all familiar with, and yet every story is unique. There is no catharsis to be found. Shrapnel fatally wounded Louis on November 3, 1918. Thirty-six days later, Louis was dead – eight days before the end of the war. The stories of frustratingly fruitless fighting and the injustice of the loss of young life resonates throughout generations.

He is buried at the Brockwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, United Kingdom. At the time of his death, Louis was a Private in the 102nd Battalion, Canadian Infantry Regiment. Louis has not been forgotten and neither have the pioneering women who fought for his life. The subsequent generations of Louis’ family line are still living in Canada.

Author: Luke Danes

‘All the hard work is done by the voluntary nurses, assisting with the dressings, making the beds, sweeping and dusting, attending to the meals, washing up, etc. They are to be specially commended – some are married women (one I know of has a husband at the front), and some are girls, and they have voluntarily turned out to do war work.’

Private Crouch, an Australian patient, describing Endell Street to his father

(Sydney Daily Telegraph, 19 November 1915)

The First World War military hospital at Endell Street in Covent Garden was best known for being the only such hospital to be run and staffed exclusively by women, led by the eminent suffragettes, surgeon Louisa Garrett Anderson and doctor Flora Murray. But what is perhaps less well known is the role played by the volunteers who assisted the specialist staff and thirty-six trained nursing sisters in almost every way imaginable, and made the hospital a resounding success in the treatment of some twenty-six thousand wounded soldiers, and a popular place for them to recover; ‘I don’t mind how many times I get wounded if they bring me back to Endell-street every time’ quipped one patient in 1916.

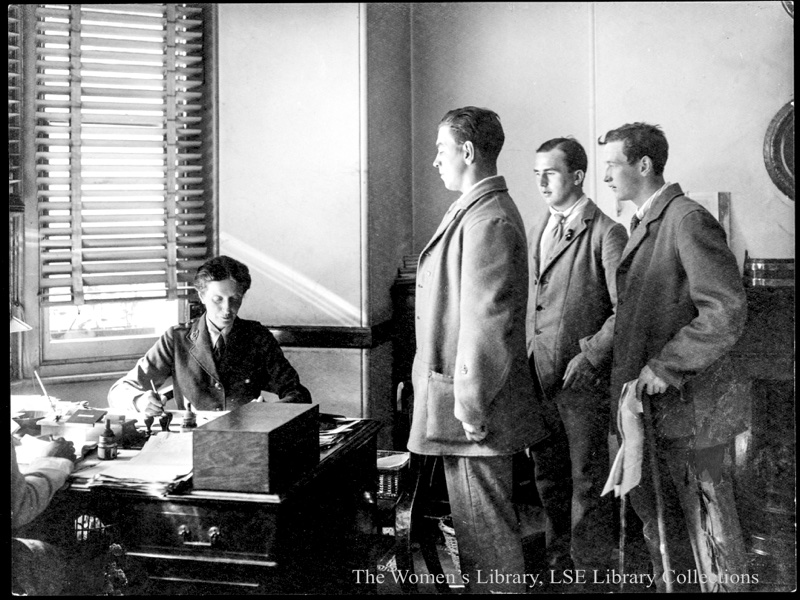

Endell Street Hospital appears to have had three main sources of volunteers: those who had previously been members of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and long-term followers of Anderson and Murray, those who had already volunteered for the Women’s Hospital Corps (WHC) at Paris and Wimereux, and those of the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). In all there were around 100 volunteers at Endell Street, ‘London society girls and women’, and they wore a unique khaki uniform specially designed by Anderson and Murray. The volunteers were referred to as ‘nurses’ and were all given the rank of ‘orderly’.

This study focuses on ten of the women of the VAD who volunteered at Endell Street at some point between the hospital’s opening in April 1915 and its closure in October 1919. The origins of the VAD itself go back to 1909/10 when the decision was taken to form a dedicated unit to deal with wartime injuries, a responsibility which had previously been undertaken by a confusing arrangement of the St John’s Ambulance Association, and latterly the Red Cross. Although not strictly an all-female organisation by any means, the VAD was nonetheless predominantly made up of well-off women from middle class backgrounds who could not possibly accept paid employment in wartime. What attracted women of such eminent social standing to a repurposed Victorian workhouse, in what The Lady’s Pictorial described as ‘a somewhat grimy thoroughfare’, was a sense of nationalism and duty, combined with chivalric idealism and pride in what they were doing.

Flora Murray described the volunteers as ‘Gently nurtured, expensively but ineffectively educated, […] unequipped and untrained’, but these women and girls gave everything that they could and in one sad instance, that included her life. These are their stories.

Alice Victoria Blake

Alice Victoria Blake was born around 1888 into a wealthy family who lived in the Hertfordshire village of Much Hadham. Alice joined the fledgling VAD in its infancy in 1910 and was to experience a busy wartime service. Her first posting was to a VAD hospital in Hampshire between October and December 1914, before being sent to a French military hospital between January and March 1915. In April she arrived back in England and volunteered at the Farnham VAD auxiliary hospital until July. In August she returned to France and volunteered at the ‘Allies Hospital’ at Yvetot until November. In January 1916 Alice returned to the VAD hospital in Hampshire, and volunteered there until April. Alice returned to France yet again in May to volunteer at the Hôpital Temporaire d’Arc-en-Barrois, and remained there until November. Alice arrived at Endell Street in July 1917 and was still serving there at the end of the war.

Nora Chance

Nora Chance was from the hamlet of Crofton, near Carlisle in Cumbria. She joined the VAD on 1 January 1914, and on 25 March 1915 started volunteering for around thirty hours per month at the newly-opened Chadwick Auxiliary Hospital in Carlisle. Her duties were to ‘assist in care of clothing and linen repairs’, and these skills were no doubt put to further use when she was seconded to Endell Street at the beginning of 1916. Nora was still volunteering at Endell Street at the end of the war, and was praised by Flora Murray for her lengthy service, ‘many months of which were spent in the operating theatre.’

Kathleen Crawford

Kathleen Crawford joined the VAD on 10 September 1915 and volunteered at Endell Street until July 1917. In November 1917 she became a motor driver for the Army Service Corps (ASC).

Helen Mary Du Buisson

Helen Mary Du Buisson was born on 29 April 1896 in Farnham, Surrey. She joined the VAD in 1915 and volunteered at Lady Onslow’s Red Cross Hospital at Clandon Park near Guildford between December of that year and June 1916. She then spent ten days at the Red Cross hospital in Carmarthen, before returning to Surrey and volunteering at the Guildford Red Cross hospital annex between August and October 1916. Helen then concentrated on training to be a masseuse at Dr Mary Coghill-Hawkes’s Swedish Institute, and registered in June 1917. Helen arrived at Endell Street in February 1918, where the masseuses played a vital role in the rehabilitation of orthopaedic injuries and ‘toiled over the patients without ceasing.’ She remained at Endell Street until April, and in May was transferred to the Red Cross hospital at Earls Colne in Essex, where she completed her service in September 1918.

Marcia Wilshire Geddes

Marcia Wilshire Geddes was born in Westminster in 1898, and by 1911 was attending boarding school at Hove in Sussex. At the start of the war Marcia was volunteering at the Swedish War Hospital in Paddington Street, Marylebone. Marcia volunteered ‘whole time’ on the wards at Endell Street between August 1915 and August 1917 whilst living in Kensington.

Gwen Isaacson

Gwen Isaacson was born in Rosslyn, Midlothian, in around 1886, and by 1901 she was living in Rugby in Warwickshire. Gwen joined the VAD in November 1914 as a Special Service Member of the Northants Detachment, and volunteered at the Hospital of St Cross in Rugby until February 1915, followed by the Thornby Auxiliary Military Hospital between July 1915 and September 1917. Gwen volunteered at Endell Street between October 1917 and July 1918 for four days a week. She went on to volunteer for three days a week at the Garland Hospital in Mayfair until 1919. On conclusion of her service, Gwen was praised by her commandant for her ‘most excellent work’ and was ‘highly recommended’.

Jane Veale Mitchell

Jane Veale Mitchell was born around 1881 and joined the VAD in 1914. Her first posting was to the No. 3 Auxiliary Hospital in Paris, followed by the Brondesbury Military Hospital in north London for two months. She then went to volunteer at the 4th Northern General Hospital in Lincoln between 1917 and 1918, before returning to London to volunteer at the Manor House Hospital, Golders Green, during May 1918. Jane volunteered at Endell Street during the second half of 1918. Her final posting was to the Seaford Sanatorium in East Sussex on 1 June 1919.

Eva Prior

Eva Prior was from Esher in Surrey, the youngest daughter of Henry Temple Prior, Master of the Supreme Court. She joined the VAD in May 1915 and volunteered at Esher Red Cross Hospital. Eva was in her second year at Endell Street when she contracted Vincent’s Angina, probably from working with infected wounds, and died soon after on 5 January 1918. In her unpublished memoirs, fellow VAD member Nina Last commented on the insanitary conditions at Endell Street, exacerbated by long hours and insufficient food, and recalled: ‘A young friend of only 21 reported sick to the home sister (a hard cruel woman) and was dead in 3 days’. Flora Murray paid tribute to Eva, saying that she was ‘loved by every one for her sweet disposition and her strength of character.’ Eva was the first of several volunteers to lose their lives at Endell Street.

Olive M Thompson

Olive M Thompson was born around 1896 in Burton-upon-Trent in Staffordshire, and joined the VAD in 1915. She initially volunteered at the VAD Red Cross Hospital in Burton-upon-Trent where her duties were described as ‘Kitchen helper’, before spending some time at Endell Street. She also worked at the Rolls Royce factory in Derby. Olive left the VAD in 1916 having volunteered for a total of 156 hours.

Agnes Mary Wood

Agnes Mary Wood was from Kensington, and spent the beginning of the war in France running her own ‘Recreation Hut under auspices of YM.CA’, before returning to England, where she joined the VAD on 5 March 1915. Between 22 February and 23 June 1917 she volunteered as a masseuse at Endell Street for three hours a day. From 1 October 1917 she was volunteering for four hours per day at the Rosslyn Lodge Auxiliary Hospital in Hampstead.

Notes

1 ‘Wounded Heroes’ Comforters’ was just one example of patients affectionately re-using the Women’s

Hospital Corps’ initials to show their appreciation to the volunteers; see Flora Murray, Women as Army

Surgeons: Being the History of the Women’s Hospital Corps in Paris, Wimereux and Endell Street, September

1914 – October 1919 (London, 1920), p. 200.

2 Daily Chronicle, 25 April 1916

3 Jennian F Geddes, ‘Deeds and Words in the Suffrage Military Hospital in Endell Street’, Medical History, Vol.

51, Issue 1, January 2007, pp. 79-98. p. 85, p. 90.

4 Sydney Daily Telegraph, 19 November 1915

5 Searching the Red Cross VAD Records (http://www.redcross.org.uk/en/About-us/Who- we-are/History- and-

origin/First-World- War) for ‘Endell’ produces fifty results and ‘Endall’, a further two. These ten women were

selected to give a wide cross section of volunteers.

6 Thekla Bowser, The Story of British V.A.D. Work in the Great War (London, 1917) second ed., pp. 20-27.

7 Henriette Donner, ‘Under the Cross – why V.A.D.s performed the filthiest task in the dirtiest war: Red Cross

women volunteers, 1914-1918’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 30, Issue 3, Spring 1997, pp. 687-704. p. 687.

8 The Lady’s Pictorial, 8 January 1916; Donner, p. 690.

9 Murray, p. 99.

10 Ancestry, all records: ‘Alice Victoria Blake’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red

Cross VAD Records: ‘Alice Victoria Blake’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]

11 Ancestry, all records: ‘Nora Chance’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red Cross VAD

Records: ‘Nora Chance’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/History- and-origin/ First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]; Murray, p. 203.

12 Red Cross VAD Records: ‘Kathleen Crawford’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]

13 Ancestry, all records: ‘Helen Mary Du Buisson’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red

Cross VAD Records: ‘Helen Mary Du Buisson’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]; Murray, p. 163. In 1928 Helen married into

the Twinings tea family and became Lady Twining. She died in 1975.

14 Ancestry, all records: ‘Marcia Wilshire Geddes’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red

Cross VAD Records: ‘Marcia Wilshire Geddes’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]

15 Ancestry, all records: ‘Gwen Isaacson’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red Cross

VAD Records: ‘Gwen Isaacson’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/History- and-origin/ First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]

16 Ancestry, all records: ‘Jane Veale Mitchell’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red

Cross VAD Records: ‘Jane Veale Mitchell’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]

17 Ancestry, all records: ‘Eva Prior’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red Cross VAD

Records: ‘Eva Prior’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/History- and-origin/First- World-War>

[last accessed 26 July 2017]; The British Journal of Nursing, Vol. 60, 12 January 1918, p. 22; Christine E Hallett,

‘Saving Lives on the Front Line’, History Today, Vol. 67, Issue 7, July 2017, pp. 24-35. p. 30; 7NLA/1/02b,

Transcript of ‘Nina’s War Memories’, (TWL@LSE), p. 10; Murray, p. 208.

18 Ancestry, all records: ‘Olive M Thompson’ <http://www.ancestry.co.uk> [last accessed 5 July 2017]; Red

Cross VAD Records: ‘Olive M Thompson’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]

19 Red Cross VAD Records: ‘Agnes Mary Wood’ <http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who- we-are/ History-and- origin/First-World- War> [last accessed 26 July 2017]