Author: Katya Creed

A huge thank you to Morgan Brewster, who got in contact with Digital Drama after picking up our project flyer in a Covent Garden pub when he was in the UK researching his great uncle Louis Daem’s story….

When Canadian Private Louis Daem arrived at the Endell Street Military hospital on the 7th November 1918, a blacksmith turned decorated war hero with shrapnel in his thigh, he was received with the same flurry of stretchers, linens and doctors that all those arriving to London hospitals from the front were familiar with. However, in this case, he was received exclusively by women.

We think we know the story, and we already know how it ends. But to get to the heart of the story, we have to go back to the beginning.

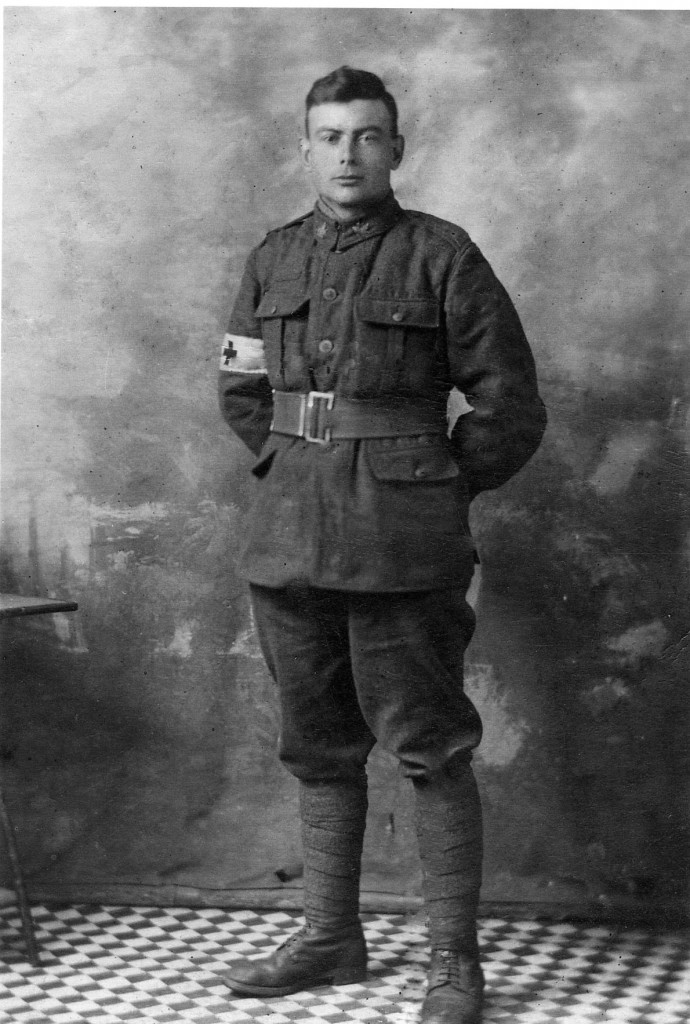

Louis Daem signed his enlistment papers and swore allegiance to His Majesty King George V in January 14, 1916 having travelled to Vancouver, B.C. He was 22 years old and had 6 siblings; 4 brothers and two sisters. At 5’ 9” tall with brown hair and brown eyes he was a striking young man. He had been working as a blacksmith prior to enlisting (a job that may have subsequently gone to a woman in absence of young men). The pay he received as a private was sent home at his request to his sister, Mary Daem.

Throughout his time at the front, Louis witnessed the very beating heart of this war, ranging from on the ground soldiering to aeroplane activity “resulting in several aerial duels.” By the age of 23 he had witnessed British planes falling in flames. The unpredictable changing pace of life at the front was no doubt disorientating. For days, he was stuck stagnant with orders to “stand to”, followed swiftly by constant aerial fighting and the subsequent difficulties of burying the wounded, maintaining the trenches and completing anti-gas precautionary measures. Every effort at all times was concentrated on successfully completing the most recently assigned tasks and missions.

On the 1st of November 1918 an intense barrage began, described as the most violent they had yet witnessed in France. The casualties were described as “frightful” with hundreds of prisoners captured. With sudden orders for assembly and movement, the battalion was moved immediately and within 30 minutes were on their way in support of the 10th Brigade. It was here that Louis earned his medal for bravery under fire.

On the 2nd of November, a concerted plan of attack was initiated, with the object of pushing back the enemy towards the east from the south of Valenciennes. The 102nd battalion fell into its place on the left flank of the 54th encountering considerable machine gun opposition. Despite this, they successfully pushed forward to their objectives, but not without casualties. Amongst these casualties was Private Daem.

Having been surrounded by bullets, shells, gas and death for two years it would be hard not to think of oneself as invincible. When there is so much to be afraid of, one stops being afraid at all. Throughout the course of his military service, Louis had been hospitalised for mumps, influenza and gonorrhoea – but this was his first and only case

Throughout those intervening days, Louis was rapidly evacuated and within 4 days had reached Brighton, passing through field hospitals and clearing stations. All of which would have been improvised structures. On the 7th of November, 5 days after being wounded, Louis was admitted to the Endell Street Military Hospital in Covent Garden. The staff noted that on admission he was “very shocked”, a reference to his shell shock, and appeared nervous. More worrying, his wounds were “very septic.” Four days after his treatment began, an armistice was signed and after 1568 days of fighting The Great War was over.

Once away from the dangers of the front, Louis was able to finally receive proper medical treatment, all of which was documented by the Endell Street doctors, orderlies and administration staff. He underwent two operations, which included an amputation. He was supplied with copious amounts of brandy in place of traditional painkillers as supplies were stretched to their limit. Louis battled his infections in this way for 32 days, but eventually succumbed to his injuries. On the 21st of November, 1918, his condition was steadily worsening. His pulse was rapid and a few days later a large abscess had formed in his thigh. The hospital administered saline intravenously, after which his pulse rate improved. A few days later on the 9th December the doctors of the Endell Street Military Hosptial operated on his wounded thigh, removing his leg in a full amputation. Despite his steady pulse and another round of saline Louis collapsed shortly after his surgery. He was recorded as having died of heart failure.

It’s a story we are all familiar with, and yet every story is unique. There is no catharsis to be found. Shrapnel fatally wounded Louis on November 3, 1918. Thirty-six days later, Louis was dead – eight days before the end of the war. The stories of frustratingly fruitless fighting and the injustice of the loss of young life resonates throughout generations.

He is buried at the Brockwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, United Kingdom. At the time of his death, Louis was a Private in the 102nd Battalion, Canadian Infantry Regiment. Louis has not been forgotten and neither have the pioneering women who fought for his life. The subsequent generations of Louis’ family line are still living in Canada.

Leave A Comment